Systemic change has been a frequent topic on this blog – as it is in my work. After running after the perfect conceptualisation of systemic change for many years, this post is inspired by my realisation that there may be different ways to look at systemic change – all correct in their own right. I have discussed systemic change with many colleagues and friends and I have always tried to reconcile different views on the concept, only now realising that they might not be reconcilable. So here an attempt of a typology of systemic change (initially differentiating two types) – nothing final, just trying to put my thinking down in writing.

A warning in advance. This article is rather conceptual and I’m introducing some models that might be new to my readers (but then again, I have done that before). I’m trying to sort through recent reading in my mind to better understand the types of systemic change. This should not stop you from reading it of course! I would be happy to discuss this with anybody!

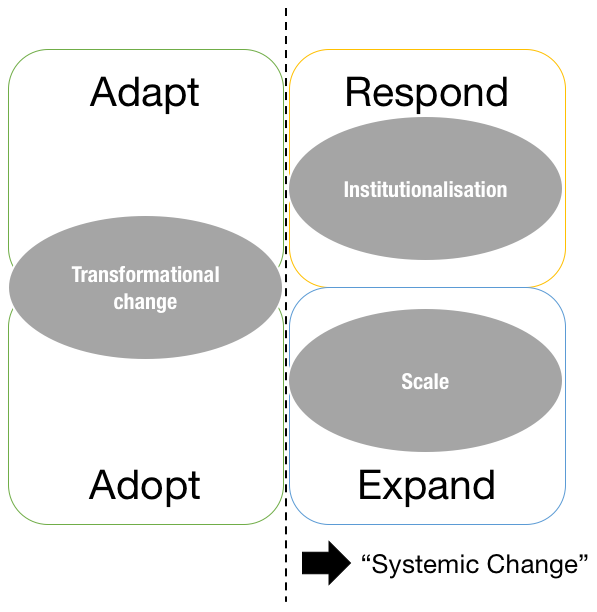

- The AAER framework superpositioned with the phases of systemic change defined in the Katalyst framework (grey ovals) – as suggested in the presentation I listened to. In the AAER framework, if an intervention reaches the Expand and Response stages, it is seen as being systemic change (arrow on the bottom of the graphic).

Recently, I listened to a presentation in which a project using a market systems approach presented its strategy to assess systemic change initiated by the project. The project uses the Adapt-Adopt-Exapnd-Respond (AAER) framework (which I have blogged about before). At the same time, they superposition the framework with language of the systemic change framework that I developed for Katalyst in Bangladesh [1], using the terms ‘transformational change’, ‘scale’ and ‘institutionalisation’ (the framework is described here and I have further developed it subsequently, described here). While I agreed that what the project has achieved can indeed be seen as systemic, I also realised that there are different types of systemic change. At the same time, I also felt that the way they superpositioned the frameworks was not coherent with my thinking. So I did some more thinking …

The AAER framework superpositioned with the phases of systemic change defined in the Katalyst framework (grey ovals) – as suggested in the presentation I listened to. In the AAER framework, if an intervention reaches the Expand and Response stages, it is seen as being systemic change (arrow on the bottom of the graphic). Source: own work

Systemic change as a scaled innovation

As I have explained in my earlier blog post, the logic behind the AAER framework is that the project introduces an innovation into a system together with one or a few local partners, usually businesses. The idea is that the innovation makes some products or services more accessible to the poor in the market – for example the introduction of a smaller, more affordable packet size of quality seeds to the market which was more appropriate to poor consumers as in the case of Katalyst. The project’s partner adopts this innovation and integrates it into its business strategy and operations, potentially adapting it along the way, for example to fit better into its operational or marketing strategy. In the expansion stage of AAER, either the partner businesses scale the innovation into new geographical areas and markets on their own and/or other competing companies copy the model. So this is reaching ‘scale’ of the type of copying and pasting something that works to reach larger numbers (this way of interpreting scale has been criticised and other ways to interpret scale have been suggested here). Finally, when the system around the innovation responds to the new way of doing things by either offering complementary services from non-competing companies or by adjusting regulations, we reach ‘institutionalisation’. In the logic of the AAER framework, if an intervention reaches the Expand and Response stages, it is seen as being systemic change.

In the presentation by the project, adoption and adaptation was interpreted as the transformational change (see illustration). The reason I found this incoherent is that, in my view, transformational change is inherently systemic, while in the AAER framework systemic change is on the right hand side. That means that ‘transformational change’, in my mind, cannot be on the left hand of the AAER framework. One would rather have to reformulate it into ‘a change/innovation that has the potential to be transformative for the system’.

I have always been sceptical about the logic behind the AAER framework, as some of my readers know. Yet I also felt during this presentation (as I did when I read these Katalyst case studies), that interventions that follow the AAER framework’s logic can still achieve some type of systemic change. So how to reconcile this confusion?

Enter sociotechnical transitions

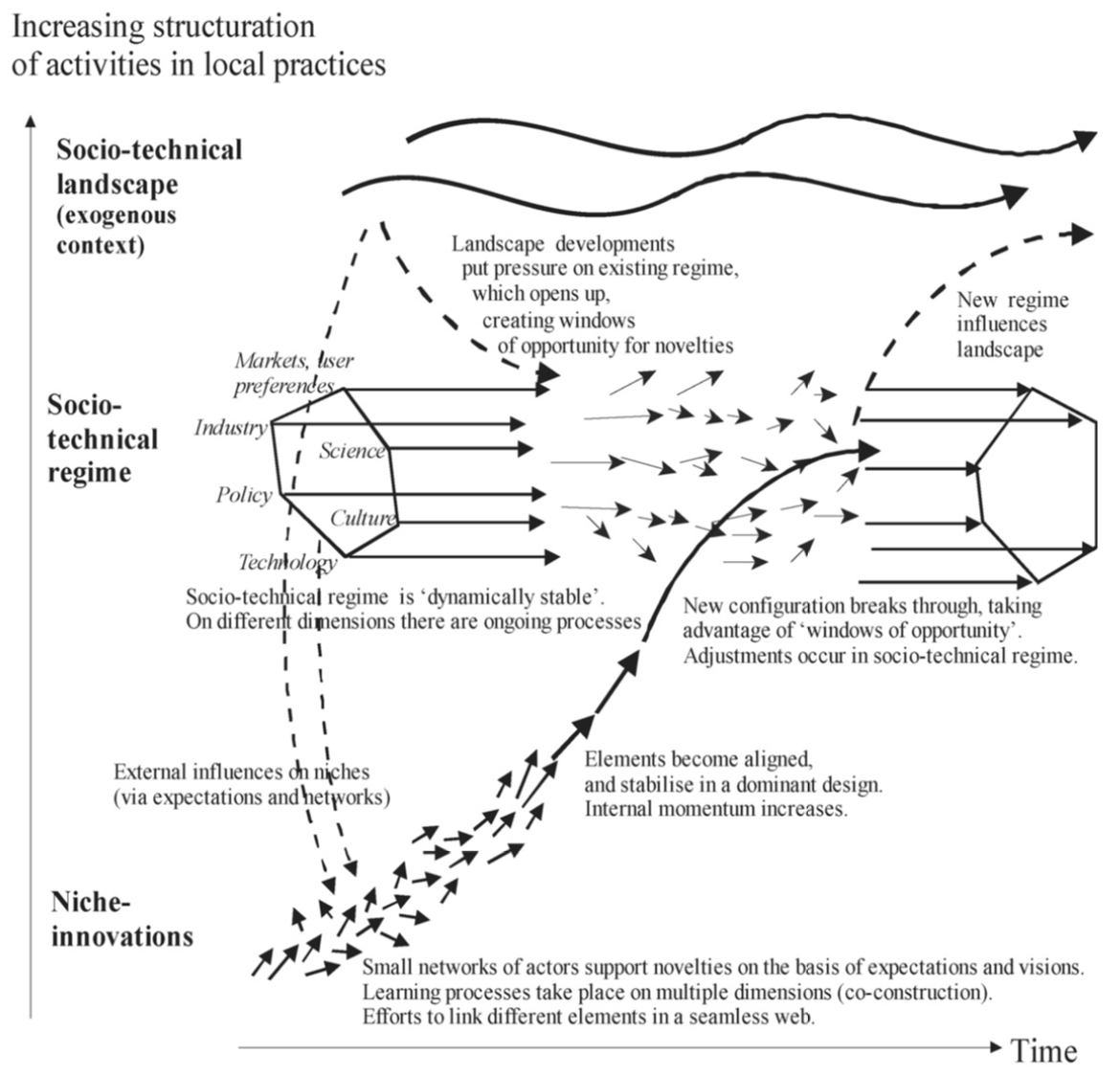

Now we get to the conceptional part, bear with me. A model that I discovered recently and found quite useful to understand transformations in systems is the concept of sociotechnical transition pathways, described by Frank Geels and Johan Schot [2] (the terms ‘transformation’ and ‘transition’ are used synonymously here). In the cited article, Geels and Shot describe a multi-level perspective (MLP) on sociotechnical systems [3]:

The MLP distinguishes three levels of heuristic, analytical concepts (Rip and Kemp, 1998; Geels, 2002): niche-innovations, sociotechnical regimes and sociotechnical landscape. … we define transitions as changes from one sociotechnical regime to another … [2:399]

The sociotechnical regime is an extended version of Nelson and Winter’s (1982) technological regime, which referred to shared cognitive routines in an engineering community and explained patterned development along ‘technological trajectories’. Sociologists of technology broadened this explanation, arguing that scientists, policy makers, users and special-interest groups also contribute to patterning of technological development (Bijker, 1995). The sociotechnical regime concept accommodates this broader community of social groups and their alignment of activities. …

Technological niches form the micro-level where radical novelties emerge. These novelties are initially unstable sociotechnical configurations with low performance. Hence, niches act as ‘incubation rooms’ protecting novelties against mainstream market selection (Schot, 1998; Kemp et al., 1998). Niche-innovations are carried and developed by small networks of dedicated actors, often outsiders or fringe actors.

The sociotechnical landscape forms an exogenous environment beyond the direct influence of niche and regime actors (macro-economics, deep cultural patterns, macro-political developments). Changes at the landscape level usually take place slowly (decades).

The multi-level perspective argues that transitions come about through interactions between processes at these three levels: (a) niche-innovations build up internal momentum, through learning processes, price/performance improvements, and support from powerful groups, (b) changes at the landscape level create pressure on the regime and (c) destabilisation of the regime creates windows of opportunity for niche-innovations. The alignment of these processes enables the breakthrough of novelties in mainstream markets where they compete with the existing regime. [2:399-400]

An illustration of the multi-level perspective described by Geels and Schot. Source: [2]

AAER starts with a niche-level innovation

Let’s think back to the process behind AAER. A project develops together with one or a few organisations a new, innovative product or business model to address some or other underperformance of the market in the way it serves the poor. Understanding the theory behind the sociotechnical transitions, such an innovation would be located on the niche level. Furthermore, it would only be able to reach scale, i.e. enter the mainstream defined by the current sociotechnical regime, if it is in line with this regime – or in other words, if it does not question the current regime.

Why is that? Following Geels and Schoot, there are two types of niche-innovations:

Niche-innovations have a competitive relationship with the existing regime, when they aim to replace it. Niche-innovations have symbiotic relationships if they can be adopted as competence-enhancing add-on in the existing regime to solve problems and improve performance. [2:406]

In the case of niche-innovations with a symbiotic relationship with the existing regime, such innovations would easily scale but at the same time they would (through problem solutions and performance improvement) potentially stabilise and strengthen the current regime.

However, Geels and Schot make it clear that even if niche-innovations have a competitive relationship with the existing regime and a window of opportunity opens, the niche level will not always be able to use opportunities created by weaknesses in the regime to introduce a new sociotechnical paradigm. The elements of the niche level need to be mature enough, become aligned and stabilise in a dominant design. Even if there is pressure on the regime to change coming from the sociotechnical landscape, if niche-innovations are not mature and organised enough, regime actors will respond by modifying the direction of development paths and of their innovation activities without putting the dominance of the regime in danger.

Two types of systemic change – the beginning of a typology?

The typical pathway described by the AAER framework builds one part of a typology on systemic change. An innovation is introduced to rectify a problem in the current regime and, as it is in a symbiotic relationship with this regime, it is quickly scaled and integrated in the regime. This type of innovations generally stabilise the regime – which is ok if one is in favour of this current regime. In this case, one would not talk about a system transition, but still about systemic change – as the innovation has reached scale and benefits many people.

Following the logic of the AAER, a change is systemic if it is scaled and institutionalised within the current sociotechnical regime. In other words, a change can be systemic without being transformational (there might be a certain adjustment in the ‘respond’ phase but this does not change the underlying paradigm of the current regime).

On the other hand, there is systemic change that is also transformational. This happens if the innovations on the nice-level are competing with the current regime and they are mature and aligned/organised enough to take advantage of a disturbance of the regime coming from the landscape level. In this case, the regime would be replaced by a new one.

Now what should we aim for, systemic change without transformation or transformation? One could argue that when looking at poverty reduction efforts, we should aim at the latter. If we only focus on introducing innovations that are symbiotic with the current regime, we might be able to scale an innovation that helps the poor in a certain way. Yet, the overarching regime that creates the situation in the first place has not changed. At the same time, one could argue that system transitions are extremely risky because one can never be sure what a system transitions into – which would be the antithesis of a ‘do-no-harm’ approach. So one could argue that development actors should aim for systemic change without transition – which again could lead to the argument that this might stabilise a regime that we don’t really support. So there is a lot to discuss here and I certainly don’t have the right answer.

We also would need to discuss how interventions would differ if they were aiming for either of the two types of systemic change. But that is material for a next blog post.

PS: I still think, thought, that ‘transformational change’ cannot be on the left side of the AAER framework …

Resources and notes

[1] I of course can only assume that this is where they have taken the terms from, otherwise its a big coincidence that they have come up with exactly the same terms … just thinking about how long it took me to decide on them.

[2] GEELS, F.W. & SCHOT, J. 2007. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, Vol. 36(3):399-417.

[3] The term ‘sociotechnical system’ might confuse some of the readers here, as the ’technical’ could be interpreted as depending on specific physical technologies. But the application of the concept of technology here is much broader. In the way the concept is applied in this knowledge domain, society itself, and most of its substructures, can be seen as complex sociotechnical systems. Indeed, the means for society to self-organises itself are often called ‘social technologies’. See for example CUNNINGHAM, S. & JENAL, M. 2016. Rethinking systemic change: economic evolution and institution. Technical paper. The BEAM Exchange.

Reminded me of First Order and Second Order change: https://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=178202

Thanks, Bhav, looks interesting!

Hi Bhav. Yes, I agree that there are similarities and the differentiation between first order and second order change is helpful. It would be interesting to translate it from an organisational context as in the article to a societal context. Best wishes, Marcus

Hi, I think the way we think is probably limited by our definitions from the beginning, or assumptions. My background is ecology and we observe transformational changes also at micro levels (for example a genetic mutation) that may or may not transform the meso level (phenotype) and/or the macro level (new behavior or ecosystem equilibrium or homeostasis).

In a development process, we may find some local transformations (at house level or community level) that may not transform the whole sociotechnical regime but making a big difference on a poverty reduction level (essentially a micro level impact). For example, in a value chain, we can transform the way women are included on a more equitable manner without transforming the whole value chain system and still stabilizing the sociotechnical regime (on a better manner for women).

So, adopting and adapting can be transformative for parts of the system without being transformative for the whole system. Do we need to institutionalize and or scale up such local transformation? Maybe if we want to “secure” such local transformation on the long term.

My reflection is rather on the “Scale” part. Do we have to scale everything? And can everything be scalable? A series of minor and localized changes transform the whole sociotechnical regime without being scaled but rather by cause-effect cascade. It is not the “size” of the change that count but the potential trickledown effect that it may have within the system. A new attitude of elders towards young people or women can make huge changes! And, as you correctly wrote, with the risk to never be sure what the system will transition to.

If I would propose a typology for systemic changes I would think about the following:

1- Systemic changes at essential level: some essential actors adopt and adapt innovations with or without scale, with or without institutionalization, but with significative impact (transformation) at household or community level (poverty reduction). The system will work better for the poor or will be stabilized for the benefit of the poor;

2- Systemic changes at support level: support actors do change the way they offer services and support for the benefit of the essential actors and /or for the benefit of targeted excluded or vulnerable essential actors… the system being more inclusive it will “work better for the poor” without changing fundamentally the way essential actors do their “usual businesses”.

3- Systemic changes at rules level: changing rules car have trickledown effects on both support and essential actors. Changing land tenure rules for example can change essential actor business models and the way support actors will design and offer their services.

I don’t know if it helps… we should not forget that there are many systems within a system: we don’t have to change the whole system to make a difference! What do we want to transform: the system or the impact the system has on some specific groups? Do we really have to change the whole system to change its impact?

Being systemic doesn’t mean staying at system level, but using the whole or part of a system for a cause, isn’t it? Being systemic means that the part that can be changed is still accepted and integrated in a system (not rejected or marginalized). If the whole system feels like scaling up a change in one of its parts for a bigger transformation, fine! If the system feels institutionalizing a change to secure it or ease its scaling up progression, fine! But it doesn’t have to be like this every time.

Dear Bernard. Thanks for your thoughtful reply. I agree that change in a system can come from everywhere. It does not have to come from a particular level. This is also reflected in the multi-level model, where change can come from the niche, the regime or the environment. But the three have to play together, transformation only happens if all three levels are enabling it.

I also agree with your assessment of scale in as far as scale is often seen as doing more of the same. In a complex system, it can be enough for a change to happen in one place to shift the whole system. The same change does not have to be replicated all over the system, cookie-cutter-style.

The typology you mention is based on the market systems development ‘donut’. For me, the three categories of core-transactions, support functions and rules and regulations are fairly arbitrary and not necessarily appropriate for a typology of systemic change. I haven’t seen these three elements reflected in any theory of economic or socio-economic change or any other school of thought on systemic change. This is why I do not use the donut much in my practice.

Thank you Marcus for your clarifications…