I had the great pleasure to talk to Chris Corrigan for another episode of the Systemic Insight Podcast (Episode 9). Chris is a facilitator and an expert in complexity-sensitive facilitation techniques. He has been using similar methods and frameworks as Mesopartner, such as for example the Cynefin framework, developed by Prof. Dave Snowden. Chris describes himself as a process artist, a teacher and a facilitator of social technologies for face to face conversation in the service of emergence. His business is supporting invitation: the invitation to collaborate, to organise, to find one another and make a difference in our communities, organisations and lives.

Chris and I talked about the difference between being an expert that brings solutions and a facilitator that creates the conditions for emergence. We discussed the importance of invitation and respecting human dignity in collaborative processes and in dialogue. During the discussion, Chris described the Cynefin framework and how he uses it in his practice. Chris presented Cynefin as an incredibly useful generative framework and shared how we can use it to make sense of action.

Chris and I also discussed the current COVID-19 pandemic, how complexity concepts suddenly become very important and useful, and we explored quite deeply the relationship between leadership, moral and ethics, complexity and decision making.

Finally, we talked about the concept of dialogue and dialogic approaches and how they are fundamentally part of how we humans make sense of the world around us, interact and collaborate, and explore different options on how to act.

As the episode is 1.5h long and not everybody might be able to put aside enough time to listen to it, below some extracts of the podcast, partly verbatim quotes by Chris, partly paraphrased by me. Hopefully this is enough of a teaser so you will still go and listen to the full episode, its well worth it!

Complex facilitation

Chris made his first experiences with truly complexity-sensitive facilitation when he started working with the Open Space technology. In Open Space, participants themselves determine the work they need to do and find one another. The core mechanic of Open Space is invitation: inviting people to gather, inviting them to make sense of their current situation and inviting them to create the invitations for action.

Beyond Open Space, in complex contexts in general, invitation creates the conditions for good attractors to catalyse different kinds of ways of being. In the most creative moments that we have, we feel invited into working together, into collaborating. Invitation acknowledges our basic human dignity and what we have to offer.

The basic way in which we work in complexity is that we need to allow, observe, pay attention. As a facilitator, our role is to create and maintain the constraints of the system, which concretely means we need to create the space within which the participants of the process can work together. The looser the constraints, the more space the participants have to create their own process and ways of getting to a solution. Creating the necessary space for participants is a different way of facilitating to when we are assuming that we as facilitators know the answers, know the process and need to keep people on task in a top-down manner. This might work in some contexts, but is not working when looking at complex issues.

Chris curates great lists of resources on facilitation and on Opens Space on his website. Another great article on complex facilitation is Sonja Blignaut’s Medium Post “Ten tips for facilitating emergent processes.“

The Cynefin framework

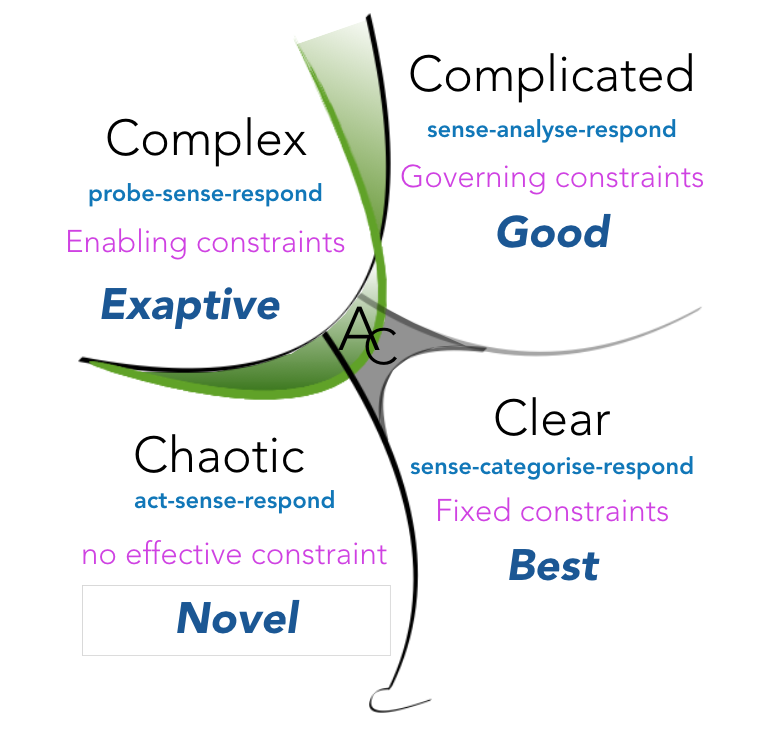

Chris recently wrote an article on the updated version of the Cynefin framework on his blog, which is one of the reasons I wanted to talk to him on the podcast. Chris is an authorised Cynefin trainer and he walked us through the Cynefin framework during the chat. For him, the Cynefin framework as an incredibly useful generative framework. It’s a decision making framework fundamentally, and it helps us to make sense of action. It helps us to make sense of what kinds of actions we need to take in order to address the kinds of problems we are facing. It works on a number of levels. The first level is the ontological level, where it describes the nature of things – how things are and how we should respond to things. Second level is phenomenological, the way we interpret the world. The third level is the epistemological level, describing the different ways of knowing about the different contexts.

The latest iteration of Cynefin has five domains, all starting with the letter C. Confused (marked AC in the illustration) in the centre is the most important domain as this is where we start from – if we weren’t confused we would not need a framework, we could just do the things we meant to do.

On the right hand side of Cynefin are two domains of ordered systems: clear and complicated, representing ordered systems. In ordered systems, cause and effect are knowable and stable. According to Chris, the difference between the clear and the complicated domain is really only whether you hold the expertise or not. An implication of this is that technical experts have a place in the world and that is to provide technical solutions that they have used before and that are repeatable or replicable for the problem you are facing now. But this only works if the problem we are looking at is complicated, not complex.

Solving a problem like racism, on the other hand, is different from solving a problem like a stuck valve in an irrigation system, it is complex. There is no end in sight to racism and it morphs and shifts and changes over time, so we have to create responses to it, rather than to create solutions to it. Solving complex problems is an infinite game. The purpose of an infinite game is just to play. The purpose of a finite game is to win or to get to the desired result. This is the benefit of using Cynefin as it creates this distinction of ordered and unordered systems.

In a complex system, when we are dealing with problems that are unpredictable, when we can’t know everything in the system, we can’t know what effect our intervention are going to have, we need to work together, we need to collaborate, we need to tell stories of what’s going on, we need to decide what’s good and what’s not good, we need to be able to monitor and track our interventions and adjust on a rapid time cycle. And there is no end to the game, our strategy is constantly evolving because the context is constantly evolving.

The response in the chaotic domain of Cynefin needs to be informed by experience and wisdom.

Constraints and attractors – and COVID-19

There are different types of constraints in systems: tight, governing, enabling. There are some a number of typologies and frameworks that describe these different types of constraints in the complex space, for example from Dave Snowden or Glenda Eoyang.

Often when working in complex systems, we create containers by establishing some sort of boundaries. These can be physical boundaries like the outline of the two Islands Chris (Bowen Island) and I (Great Britain) live on. But often these boundaries are conceptual, for example defining who belongs in the group we are working with and who does not. Within the container created by the boundaries, there are a number of attractors around which action coalesces. Attractors are like gravity wells. If you live inside a container there is a pattern that’s repeating, where lots of stuff is going on. Inside containers there are connections and relationships between people, and across these connections, exchanges are flowing. In complexity we need to understand how constraints enable self organisation and emergence by looking at the attractors and the boundaries that create the space in which agents are connected and exchange. Some of these constraints can be managed, which then shapes the way people self-organise.

Some constraints during the current COVID-19 pandemic are applied from the top down and some are emergent. The constraints on movement has created the conditions for a completely different set of connections between people. If we loosen constraints, we discover new behaviour. That’s what innovation is. Innovation is about the loosening of the stabilising constraints so we can discover new things. And when we discover something cool we can stabilise it by applying tighter constraints. In the case of COVID-19, the constraints that were loosened for many are around how and where we do our work. In facilitation, innovation happens through releasing some of the constraints while tightening some other constraints as seen for example in design sprints. A good innovation process should not allow you to unsee the better futures that you’re missing by just going back to how it was before the loosening of constraints.

Identity is another important type of constraint in human systems – physical systems and biological systems don’t have identity – particles in physics or deer in the forest don’t have identity.

What to do if you don’t know what to do – integrity in leadership

In complex situations we generally don’t have a recipe on what to do, we often don’t know. This is even more exacerbated in times of chaos, when firm action is needed to reestablish some stability, but what action that is is not known. When working insect situations, we need to look at morality and ethics if we want to decide what it means to ‘make things better’. Crises show which people are moral and good and which people aren’t – you can see the core quality of people during crises. You can see what their motives are, if they have everybody’s safety in mind or mainly want to exploit the situation and improve their power. Contrasting examples are Scotland First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern compared to Donald Trump or Boris Johnson. During the podcast Chris and I unpacked this question of integrity in leadership quite a bit during the podcast episode, it is worth listening to. We also discussed the observation that the current COVID-19 crisis is threatening the established patriarchate, as it seems that female leaders are reacting in much better ways to the crisis than their male counterparts.

On dialogue

Planning in uncertainty is difficult, things need to be kept open. And if you keep things open, you need to be able to talk to each other and find out what is good and what isn’t good and which ethics guide our decisions. This is a core of dialogue.

Dialogue is about making meaning together. Dialogue is practically built into our human physiology and is part of our evolution as a species. Because our brain is so trained to see patterns we need other people to see a whole picture and to have our patterns challenged so we don’t end up in a situation where we only see the world through the lens of our patterns and our biases. The patterns we perceive and our biases create a stable reality for us and when this falls away we don’t know what to do. This stability needs to be continuously challenged through calibrating it with a diverse group of people. Dialogue is the way in which human beings work together to create resilience.

Dialogical organisational development builds on how humans make sense of the world. In contrast, the people applying traditional diagnostic organisational development would come in, diagnose the organisation and give recommendations on how it can be improved – which is fundamentally at odds with complexity. A dialogic approach to organisational development creates conditions in which people who are confronting a problem or who are stranded with the usual way they are doing things can create new ways. The tools of dialogic interventions are ancient: storytelling, noticing, curiosity. So what good dialog does is it unleashes the inherent creativity of human beings.

Any change process starts with a dialogue between people to calibrate their perception on something that is not going right or that needs to be solved or change. From a Cynefin perspective, this is initially happening in the confused domain, before figuring out what type of problem you are facing. But going beyond that, in very few places other than the clear domain, things can be solved without dialogue. Even in the complicated domain, experts might not have the exact same solution and which solution applies might need to be figured out by experts talking to each other or by us listening to different opinions of experts.

A question that is often asked is how we move from dialogue to action and results? According to Chris, it depends on the purpose. If it is about choosing between two different option of technology, we know how the output of the process needs to look like and the process is successful and done when the choice has been made – if that is not the case you need to change what you are doing. In the complicated domain, the defined outputs of a process are very tangible and can easily be described. In the complex there are also outputs, but they can be highly qualitative and maybe vague. For Chris, dialogue is action in that engaging in dialogue actually begins to fundamentally change. People talking to each other can lead to change.

Getting good at trusting one another, at being friends, at collaborating well, at making meaning together – it doesn’t mean avoiding conflict, it means engaging in a way that is resilient – is a critical feature in dialogic practice. This is what you are robbed of when consultants come in and give you a solution. The system looses its ability to depend on each other and then becomes dependent on the consultant.

What is action? What is a decision? Søren Kierkegaard said “the instance of a decision is a madness”. We make decisions when our past knowledge and our past experience and everything we have understood about a situation has failed us. The problem with people who have problems in making decisions is that they think they need certainty about the outcomes and what is going to happen next. The great decision makers make decisions in the absence of that certainty. They are guided by their moral centre, by what they think it is good; and they are guided by a sense of trust and relationship and that if they make a decision they make a decision together with others and they will be together as a team. There is no way to know if you are making the right decision. There is always a wrong decision to make, but there is no way of knowing that the one you are making is right. If the necessary trust is not there in a team, you won’t get to action.

Action is not just contextualised by the type of problem we are working on but it also happens in time. Poor action and poor execution are not always the result of an instant of a decision or the instance of a process. It could be that the historic context has been in place to produce a non-trustworthy environment.

At the end of the episode, Chris and I had a fascinating discussion about dialogue on different scales. While for most of history, dialogue only happened among people in relatively small groups, nowadays there is a global dialogue among people that happens on social media. Yet this dialogue is heavily manipulated. Artificial intelligence is playing with patterns of meaning in the dialogue. Bots are hijacking the scale of the global dialogue where the scale is so vast you can only really see patterns with an algorithm. So the meaning making at that scale is no longer ours, it’s no longer human. The way human beings have always made the bigger meaning is by not scaling and talking to more people but having more smaller conversations.

It was a great discussion and I thoroughly enjoyed it. If you are curious to hear it in full, listen to it here. You can also find the podcast on Apple Podcast or Spotify, just search for ‘Systemic Insight Podcast’.

Featured image by Papaioannou Kostas on Unsplash