Owen Barder, Senior Fellow and Director for Europe of the Center for Global Development last week posted a talk online, adapted from his Kapuściński Lecture of May 2012, in which he explores the implications of complexity theory for development policy (the talk is also available as audio-only version on the Development Drums podcast).

The talk tells a persuasive story of what has gone wrong in international development and in the various models of growth it used; that the adoption of the concepts of adaptation and co-evolution allow for much more accurate models; a brief description of complex adaptive systems and complexity theory; and what consequences these insights have for development policy. But these positive turns in development come for a price: we can no longer ignore that we – the developed nations – are also a part of the larger system and that our (policy) actions strongly influence the development potential of poor countries. It is no longer enough to ‘send money’ and experts and think that this will buy us out of our responsibilities towards those countries.

I want to quickly summarize what I think are the key points of Owen’s presentation, starting with what seems to me an obvious point:

Development is not an increase in output by an individual firm; it’s the emergence of a system of economic, financial, legal, social and political institutions, firms, products and technologies, which together provide the citizens with the capabilities to live happy, healthy and fulfilling lives.

Owen talks about various (economic) models and theories that have neglected this systemic perspective and, subsequently, failed to deliver successes in development. The focus of the economic models shifted over the years from providing capital and investment to technology.

Since this approach of ‘provision’ did not work out, the lack of favorable policies was blamed for hindering the market to achieve its theoretical potential. As a consequence, the Washington Consensus introduced which policies needed to be adopted by a country to be able to grow. As we know, this also did not work out, although the Washington Consensus did, according to Owen, have some positive impacts in developing countries.

After the Washington Consensus, development agencies focused on weak institutions and spent (and are still spending) huge amounts of money on institutional strengthening and capacity building initiatives. The results have been modest. Adding to the difficulties is the fact that it is still not clear which institutions are really important for development.

Most recently, a new book published by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (Why Nations Fail) promotes politics as culprit of failing development. According to them, the institutions are weak because it actually suits the elite that is in power to run them like this [what an insight …!!!]

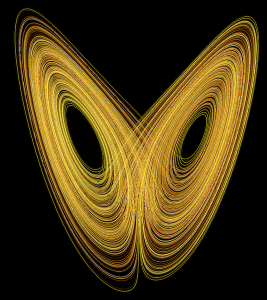

All these models that were applied were actually based on traditional economic theory. After seeing all these approaches fail, Owen switches to a new way of describing economic development, based on adaptation and co-evolution in complex adaptive systems.

After making a compelling argument why complexity theory can actually better describe the real economy out there, Owen describes seven policy implications deducted from that insight.

- Resist engineering and avoid isomorphic mimicry. The first point mainly stems from the fact that solutions developed through evolution generally outperform design. The latter point mainly implicates that institutions that were mainly built after a blueprint following ‘best practices’ but do not connect to the local environment will have not much use.

- Resist fatalism. Development should not be seen as a pure Darwinian process. Smart interventions by us can accelerate and shape evolution.

- Promote innovation.

- Embrace creative destruction. Innovation without selection is no use. Feedback mechanisms to force performance in economic and social institutions are necessary.

- Shape development. The fitness function which the selective pressure enforces should represent the goals and values of a community.

- Embrace experimentation. Experimentation should become a part of a development process.

- Act global. We need to make a bigger effort to change processes that we can control, for example international trade, the selection of leadership in international organization, etc.

Owen is not telling any news in his presentation, but he succeeds to develop a compelling storyline on why complexity theory is relevant for development and why processes that are based on adaptation and co-evolution much better describe why some countries develop while other seem stuck in the poverty trap.

In my view this is an immensely important contribution to the discussion on how we can reform the international aid system to live up to our responsibility of enabling all people on this planet to live happy and fulfilled lives.

For the last years I have had the privilege to take part of and contribute to Mesopartner’s journey into the field of complexity. We started to dismantle and question almost every aspect of our instruments, tools and theories. This journey has been very much in line with my own work, pondering how complexity theory can contribute to making economic development more effective and sustainable.

For the last years I have had the privilege to take part of and contribute to Mesopartner’s journey into the field of complexity. We started to dismantle and question almost every aspect of our instruments, tools and theories. This journey has been very much in line with my own work, pondering how complexity theory can contribute to making economic development more effective and sustainable.