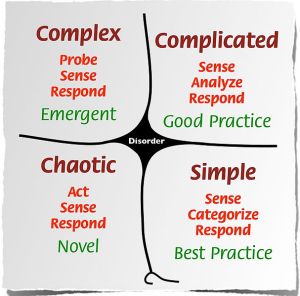

The last week of June I had the privilege of attending a three-day training event with Dave Snowden, founder of Cognitive Edge and “mental father” of the Cynefin framework. For me this was a great experience and although I had read a lot of stuff around complexity (also by Dave), there were still many new insights I got. Some things were new, others just became clearer. One thing that I knew but that was becoming more pronounced during the training is the differentiation between best/good practice and emergent practice. Continue reading

The last week of June I had the privilege of attending a three-day training event with Dave Snowden, founder of Cognitive Edge and “mental father” of the Cynefin framework. For me this was a great experience and although I had read a lot of stuff around complexity (also by Dave), there were still many new insights I got. Some things were new, others just became clearer. One thing that I knew but that was becoming more pronounced during the training is the differentiation between best/good practice and emergent practice. Continue reading

Tag Archives: complexity

Redesigning aid for complex systems

Before venturing into an outline of a results measurement framework I want to point out two blog posts by Duncan Green on aid in complex systems that are very well written and to the point. Continue reading

Presenting the Systemic M&E Initiative at MPEP Seminar

I will be presenting the Systemic M&E Initiative at the upcoming MPEP Seminar on Thursday, April 25 in Washington DC. You can either participate in person or via Webinar. More information on the event and the possibility to register can be found here.

I will be presenting the Systemic M&E Initiative at the upcoming MPEP Seminar on Thursday, April 25 in Washington DC. You can either participate in person or via Webinar. More information on the event and the possibility to register can be found here.

The presentation will have two parts. In the first part, I will present a general introduction to systems and complexity and why this is relevant for our work in development. In the second part, I will feature the seven principles we derived from the practitioner discussions during the Systemic M&E initiative.

ODI paper on planning and strategy development in complex situations

ODI just published a great paper by Richard Hummelbrunner and Harry Jones titled “A guide for planning and strategy development in the face of complexity.” It is a great piece that takes the discussion around harnessing complexity for more effective development to a much more concrete, practicable and practitioner friendly level.

In the relatively short (12 pages) and easy to read paper, Hummelbrunner and Jones introduce complexity, name the biggest challenges in the face of complexity, propose three core principles to face them, and even showcase a number of tools that can be applied in these situations.

Solutions For Building More Effective Market Systems

This blog post was originally published on the Website of CGAP, an independent policy and research center dedicated to advancing financial access for the world’s poor. The Blog post was part of the Systemic M&E initiative I worked on for the SEEP Network.

There is a controversy brewing among systems and complexity thinkers. Is it useful to define a future goal towards which our initiatives strive? Or is it wiser instead to focus our attention on what we know we can change and trust that this will eventually lead us to a future that is better than any we could have anticipated? While the first feels intuitively right to many development practitioners, proponents of the latter argue that the absence of defined goals and targets may lead to future possibilities that are more sustainable and resilient (and that could not be fully anticipated). So the question is: can we know in advance what the best (or a good) outcome will be? Continue reading

There is a controversy brewing among systems and complexity thinkers. Is it useful to define a future goal towards which our initiatives strive? Or is it wiser instead to focus our attention on what we know we can change and trust that this will eventually lead us to a future that is better than any we could have anticipated? While the first feels intuitively right to many development practitioners, proponents of the latter argue that the absence of defined goals and targets may lead to future possibilities that are more sustainable and resilient (and that could not be fully anticipated). So the question is: can we know in advance what the best (or a good) outcome will be? Continue reading

Do we need a goal or is virtue sufficient purpose?

David Snowden has written on his blog about purpose and virtue (more specifically here, here, here and here). I find it a fascinating line of thought, but still cannot wrap my head around it completely. The basic idea is that in contrast to systems thinking, where an idealized future is identified and interventions aim to close the gap to this future, complexity thinking (or at least the one advocated by Snowden) focuses on managing in the present and with that enabling possible futures to emerge or evolve that could not have been anticipated. Now the latter, the management without a specific goal, of course, asks for a purpose or motivation. Why should we bother, if we don’t have a goal? Continue reading

Knowledge Management in complex adaptive systems

How does systems thinking and complexity theory help us in designing a global knowledge management facility?

A global knowledge management facility has the goal to manage knowledge within a specific community of practice in order to improve the application of that knowledge in general or of a specific approach in particular. From a traditional point of view, important activities of such a facility would be to collect and codify knowledge, analyze good practices and there might even be a wish for standardization of the application of this particular knowledge or approach. In this sense, the facility can be seen as a custodian of the ‘right’ knowledge and oversee and certify the quality of its application. It would guard the rigor or ‘pureness’ of application of the specific approach with a view to preserve or improve its effectiveness and efficiency.

With this picture in mind I read a chapter in a knowledge management book that describes implications of systems thinking and complexity theory on knowledge management from an organizational perspectives (Bodhanya 2008). I would like to apply the conclusions of the article to the design of such a global knowledge management facility.

In his article, Bodhanya describes differences in characterizing knowledge that stem from a number of debates within the scientific community revolving around the interplay between ontology and epistemology or, to put it in simpler terms, between perspectives of knowledge as a thing and knowledge as a dynamic process. According to Bodhanya, the current debates in knowledge management, however, reduce this pluralism of the discussion around knowledge because the dominant discourse is based on what he calls a cognitive-possession perspective. He terms this ‘first order knowledge management’.

First order knowledge management is built on the following assumptions (Bodhanya 2008:7):

- Knowledge is reified.

- Knowledge is useful when it is objective and certain.

- Distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge.

- Knowledge may be managed through knowledge management.

- Knowledge identification is a search process.

- Knowledge construction is a process of configuration.

- Knowledge management comprises knowledge processes such as identification, generation, codification, and transfer.

- Business strategy may be formulated and implemented. This is a fundamental assumption across all strategic choice approaches to strategy and, at a minimum, will include the design, planning, positioning, and cultural schools of strategy.

- Knowledge management strategy may be formulated and implemented.

- Knowledge management strategy must be aligned to the business strategy.

The concept of first order knowledge management seems in line with the goals and traditional activities of a global knowledge management facility as described above: “Ultimately, first order KM relies on knowledge processes such as knowledge identification, generation (or more accurately configuration), codification, capture, and transfer in order to develop human and social capital, as these are considered as important in facilitating productive activity” (Bodhanya 2008:8).

In his paper, Bodhanya argues against the view of knowledge as a thing and criticizes current knowledge management of gross oversimplifications by relying on a view on knowledge as something that can be possessed. He suggests that knowledge is a much more dynamic phenomenon and suggests instead to shift the focus from knowledge to the act of knowing itself. “Knowledge is only generated in the act of knowing; everything else is information. In other words there is the perpetual potentiality for knowledge generation, but this is only transformed into actuality when information comes into contact with the human intellect. This happens in the act of knowing in the instant when there is sensemaking and interpretation. (…) [H]uman actors are constantly engaged in thought, and hence are engaged in sensemaking and interpretation at every instant, so knowledge is being regenerated afresh at every instant. This phenomenon of constant thought and action means that there is perpetual regenerating of knowledge” (Bodhanya 2008:10). Based on these insights, Bodhanya constructs a ‘second order knowledge management’ that takes into consideration the dynamic interplay between knowledge and the knower. In second order knowledge management, he points out, more attention needs to be paid to the social interactions between actors.

Bodhanya then details out how this view on knowledge and knowing is in line with systems thinking and complexity theory. An interesting debate he touches upon is the question who, from an organizational point of view, are the actors in a complex adaptive system of knowledge. The most obvious choice would be the individuals in an organization but another possibility is, for example, to see narrative themes as the actors. Bodhanya argues for a more nuanced view that includes the individuals as well as other forms of agents such as groups of individuals, departments, and human artifacts. He defines the systems of knowledge as ‘knowledge ecologies’: “A knowledge ecology is a dynamic system of heterogeneous agents that interact with each other according to their schemata. The schemata are inextricably linked to each agent’s propensity for interpretation and sensemaking on an on-going basis. Since interpretation and sensemaking are related to knowing in action, every act of interpretation and every act of sensemaking is in effect an actor creating knowledge. There are therefore multiple cognitive feedback loops being generated which in turn refresh the schemata according to which agents then act” (Bodhanya 2008:14). But he goes even further and looks for evolutionary tendencies in knowledge ecologies to an effect that knowledge structures become the primary agents that survive, vary, mutate, and are subject to retention and selection. There are, thus, various layers of interacting and interconnected complex adaptive systems with various types of actors at play, which makes the description – or prediction – of the system impossible.

Whereas first order knowledge management is based on a strategic choice view of business strategy, considerations of complexity and systems thinking show that the knowledge environment is far to complex for any one person to fully understand and, hence, to make strategic choices. This does not only change the view on knowledge management, but on business strategy itself; it shows the need for a more dynamic approach that is much more process oriented. “Alignment between business and knowledge management strategies may therefore not simply be designed and imposed, but may only be stimulated through managing organisational context and the interactions between actors within an outside the organisation. We may therefore also refer to business and knowledge management strategies as undergoing a process of co-evolution” (Bodhanya 2008:15).

What does this mean for knowledge management? First of all we have to realize that knowledge management does not have something to do with control over knowledge and its use. No single agent in a complex adaptive system can stand outside the system and direct it. “[M]anagerial orientations must shift from a preoccupation with the ordered, rational, analytical, and the fixed towards a tolerance of ambiguity, subjectivity, flux, and the transient nature of organisational life” (Bodhanya 2008:17). But this also means that there is no formula, recipe, or easy prescription on how to implement knowledge management. Rather, the conditions for the emergence of knowledge ecologies need to be developed. “The best that we can do is to facilitate rich interconnections between agents, increase agent diversity, and provide an enabling context for sensemaking and interpretation” (Bodhanya 2008:17). Bodhanya introduced an approach to second order knowledge management he calls strategic conversation, but he also points out that there is still a lot of research needed to fundamentally transform knowledge management into a systemic process co-evolving with other strategies within an organization.

One important piece of wisdom Bodhanya gives us for that journey: “As human actors and managers, we are in a sense deluded by the extent to which we think we are in control. It calls for increased humility on the part of all of us as human actors. In a systemic world, we control less than we think, because the effects of our actions are subject to many feedback loops and nonlinear responses that are outside our sphere of influence and control. (…) Our plans are merely artifacts, and to the extent that they contribute to co-evolution, they do have a valuable role. However, this may call into question our criteria for what the value of a plan is, and what constitutes a good or a bad plan” (Bodhanya 2008:19).

What does this all mean for a global knowledge management facility? Obviously, such a facility does not follow the same rules as an organization, which can be seen as complex adaptive system with a fairly obvious, if also penetrable, boundary. Knowledge sources are much more widespread and part of diverse organizations with their own agendas. One of the first insights, thus, must be that such a facility cannot exist on its own, observing, collecting knowledge, codifying it, and defining best practices, which it will then disseminate again into the system. Rather than a centralized secretarial-type entity, the facility should rather be a hub of a network of actors in the knowledge ecology with the aim to stimulate knowledge creation and exchange. As pointed out by Bodhanya, an essential step thereby is to “facilitate rich interconnections between agents, increase agent diversity, and provide an enabling context for sensemaking and interpretation” (Bodhanya 2008:17). So rather than to see the facility as a kind of library and custodian of the right kind of reified knowledge or the pure way of implementing an approach, it should much more be a place where discussions are stimulated and the knowledge is created while it is used. Thereby, diversity plays a big role. It is important to see that there is not one right way to implement an approach, but that knowledge is created from the diversity of its application.

This is just the beginning of a possible discussion and many things still need to be touched upon and many critical points in the assessment above need to be made visible and discussed. I hope, however, that this post provides some food for thought.

Reference: Shamim Bodhanya (2008): “Knowledge Management: From Management Fad to Systemic Change”. In: Abou-Zeid, El-Sayed: “Knowledge Management and Business Strategies: Theoretical Frameworks and Empirical Research.” Information Science Reference. Hershey, New York.

Owen Barder on Development and Complexity

Owen Barder, Senior Fellow and Director for Europe of the Center for Global Development last week posted a talk online, adapted from his Kapuściński Lecture of May 2012, in which he explores the implications of complexity theory for development policy (the talk is also available as audio-only version on the Development Drums podcast).

The talk tells a persuasive story of what has gone wrong in international development and in the various models of growth it used; that the adoption of the concepts of adaptation and co-evolution allow for much more accurate models; a brief description of complex adaptive systems and complexity theory; and what consequences these insights have for development policy. But these positive turns in development come for a price: we can no longer ignore that we – the developed nations – are also a part of the larger system and that our (policy) actions strongly influence the development potential of poor countries. It is no longer enough to ‘send money’ and experts and think that this will buy us out of our responsibilities towards those countries.

I want to quickly summarize what I think are the key points of Owen’s presentation, starting with what seems to me an obvious point:

Development is not an increase in output by an individual firm; it’s the emergence of a system of economic, financial, legal, social and political institutions, firms, products and technologies, which together provide the citizens with the capabilities to live happy, healthy and fulfilling lives.

Owen talks about various (economic) models and theories that have neglected this systemic perspective and, subsequently, failed to deliver successes in development. The focus of the economic models shifted over the years from providing capital and investment to technology.

Since this approach of ‘provision’ did not work out, the lack of favorable policies was blamed for hindering the market to achieve its theoretical potential. As a consequence, the Washington Consensus introduced which policies needed to be adopted by a country to be able to grow. As we know, this also did not work out, although the Washington Consensus did, according to Owen, have some positive impacts in developing countries.

After the Washington Consensus, development agencies focused on weak institutions and spent (and are still spending) huge amounts of money on institutional strengthening and capacity building initiatives. The results have been modest. Adding to the difficulties is the fact that it is still not clear which institutions are really important for development.

Most recently, a new book published by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (Why Nations Fail) promotes politics as culprit of failing development. According to them, the institutions are weak because it actually suits the elite that is in power to run them like this [what an insight …!!!]

All these models that were applied were actually based on traditional economic theory. After seeing all these approaches fail, Owen switches to a new way of describing economic development, based on adaptation and co-evolution in complex adaptive systems.

After making a compelling argument why complexity theory can actually better describe the real economy out there, Owen describes seven policy implications deducted from that insight.

- Resist engineering and avoid isomorphic mimicry. The first point mainly stems from the fact that solutions developed through evolution generally outperform design. The latter point mainly implicates that institutions that were mainly built after a blueprint following ‘best practices’ but do not connect to the local environment will have not much use.

- Resist fatalism. Development should not be seen as a pure Darwinian process. Smart interventions by us can accelerate and shape evolution.

- Promote innovation.

- Embrace creative destruction. Innovation without selection is no use. Feedback mechanisms to force performance in economic and social institutions are necessary.

- Shape development. The fitness function which the selective pressure enforces should represent the goals and values of a community.

- Embrace experimentation. Experimentation should become a part of a development process.

- Act global. We need to make a bigger effort to change processes that we can control, for example international trade, the selection of leadership in international organization, etc.

Owen is not telling any news in his presentation, but he succeeds to develop a compelling storyline on why complexity theory is relevant for development and why processes that are based on adaptation and co-evolution much better describe why some countries develop while other seem stuck in the poverty trap.

In my view this is an immensely important contribution to the discussion on how we can reform the international aid system to live up to our responsibility of enabling all people on this planet to live happy and fulfilled lives.

Flipping through my RSS feeds

![]() After three weeks of more or less constant work, I’m finally having some time to have a look at my RSS feeds. After the first shock of seeing more than 3000 new entries, containing over 100 unread blog posts, I just started reading from the top. Here a couple of things I found interesting (not related to any specific topic):

After three weeks of more or less constant work, I’m finally having some time to have a look at my RSS feeds. After the first shock of seeing more than 3000 new entries, containing over 100 unread blog posts, I just started reading from the top. Here a couple of things I found interesting (not related to any specific topic):

SciDevNet: App to help rice farmers be more productive – I don’t know about the Philippines, but I haven’t seen many rice farmers in Bangladesh carrying a smartphone (nor any extension workers for that matter).

Owen abroad: What are result agenda? – An interesting post about the different meanings of following a ‘results agenda’ for different people, i.e., politicians, aid agency managers, practitioners, and (what I call) ‘complexity dudes’. I’m not very satisfied with Owen’s assessment, though, because I think he is not giving enough weight to the argument that results should be used to manage complexity. I think to manage complexity, we don’t need rigorous impact studies, but much more quality focused results regarding the change we can achieve in a system and the direction our intervention makes the system move.

xkcd: Backward in time – an all time favorite cartoon of mine, here describing how to make long waits pass quickly.

Aid on the Edge: on state fragility as wicked problem and Facebook, social media and the complexity of influence – Ben Ramalingam seems to be back in the bloggosphere with two posts on one of my favorite blogs on complexity science and international development. In the first post, he explores the notion of looking at fragile states as so called ‘wicked problems’, i.e., problems that are ill defined, highly interdependent and multi-causal, without any clear solution, etc. (see definition in the blog post). Ben concludes that the way aid agencies work in fragile states needs to undergo fundamental change. He presents some principles on how this change could look like from a paper he published together with SFI’s Bill Frej last year.

In the second piece Ben looks into the complex matter of how socioeconomic systems can be influenced, and how this can be measured, by giving an example of Facebook trying to calculate its influence on the European economy and why its calculations are flawed. The basic argument is that one’s decision to do something is extremely difficult to analyze and even more difficult to trace back to an individual influencer. Also our decisions and, indeed, our behavior, are complex systems. One of the interesting quotes from the post: “Influentials don’t govern person-to-person communication. We all do. If society is ready to embrace a trend, almost anyone can start one – and if it isn’t, then almost no one can.”

Now, to make the link back to Owen’s post mentioned above on rigorous impact analyses: how can we ever attribute impacts on a large scale to individual development programs or donors if we cannot measure the influentials’ impact on an individual’s behavior? I rather like to think of a development program as an agent poking into the right spots, the spots where the system is ready to embrace a – for us – favorable trend. But then to attribute all the change to the program would be preposterous.

Enough reading for today, even though there are still 86 unread blog posts in my RSS reader, not the least 45 from the power bloggers Duncan Green and Chris Blattman. I’ll go and watch some videos now of the new class I recently started on Model Thinking, a free online class by Scott E Page, Professor of Complex Systems, Political Science, and Economics at the University of Michigan. Check it out: http://www.modelthinking-class.org/

For people with less time, a couple of participants are tweeting using #modelthinkingcourse

Exploring the science of complexity

This blog post is about what I see as one of the most important papers linking the complexity sciences to development and humanitarian efforts – at least it is for me personally, but I think it also takes a very important position in the discussion in general.

This blog post is about what I see as one of the most important papers linking the complexity sciences to development and humanitarian efforts – at least it is for me personally, but I think it also takes a very important position in the discussion in general.

The paper has the title ‘Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts’ and is authored by Ben Ramalingam (author of the blog Aid on the Edge of Chaos) and Harry Jones with Toussaint Reba and John Young. The paper can be downloaded here.

Why do I think is the paper so important? For me personally it was the first paper I read that explicitly linked the two domains (complexity science and international development) and it does that in a very comprehensive and systematic manner.

Ramalingam and colleagues go back to the origins of complexity sciences and put it into context by showing applications in the social, political and economic realms. They unpack the complexity sciences and present them in ten key concepts divided into three sets, i.e., complexity and systems, complexity and change, and complexity and agency. Here an overview taken from p 8. of their paper:

Complexity and systems: These first three concepts relate to the features of systems which can be described as complex:

- Systems characterised by interconnected and interdependent elements and dimensions are a key starting point for understanding complexity science.

- Feedback processes crucially shape how change happens within a complex system.

- Emergence describes how the behaviour of systems emerges – often unpredictably – from the interaction of the parts, such that the whole is different to the sum of the parts.

Complexity and change: The next four concepts relate to phenomena through which complexity manifests itself:

- Within complex systems, relationships between dimensions are frequently nonlinear, i.e., when change happens, it is frequently disproportionate and unpredictable.

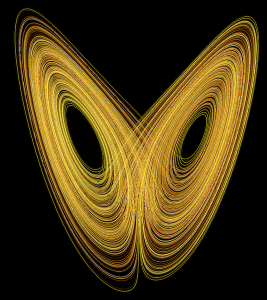

- Sensitivity to initial conditions highlights how small differences in the initial state of a system can lead to massive differences later; butterfly effects and bifurcations are two ways in which complex systems can change drastically over time.

- Phase space helps to build a picture of the dimensions of a system, and how they change over time. This enables understanding of how systems move and evolve over time.

- Chaos and edge of chaos describe the order underlying the seemingly random behaviours exhibited by certain complex systems.

Complexity and agency: The final three concepts relate to the notion of adaptive agents, and how their behaviours are manifested in complex systems:

- Adaptive agents react to the system and to each other, leading to a number of phenomena.

- Self-organisation characterises a particular form of emergent property that can occur in systems of adaptive agents.

- Co-evolution describes how, within a system of adaptive agents, co-evolution occurs, such that the overall system and the agents within it evolve together, or co-evolve, over time.

In great detail they explain every concept, give examples and discuss the implications of the concepts for the development system.

I like the paper because it really brings together all those important concepts in an accessible way. Although the paper is pretty long (89 pages all in all), it is not at all a boring read. In the conclusion part of the paper, the authors also describe the difficulty of presenting such an intricate matter as complexity sciences, itself being not a unified scientific discipline:

[…] it is useful to note that scientific knowledge is usually characterised with reference to the metaphor of a building. The ease with which the terms ‘foundations’, ‘pillars’ and ‘structures’ of knowledge are used indicates the prevalence of this architectural metaphor. Our difficulty was in trying to represent complexity science concepts as though they were parts of a building. They are, in fact, more like a loose network of interconnected and interdependent ideas. A more detailed look highlights conceptual linkages and interconnections between the different ideas. The best way to see how they fit together in the development and humanitarian field would be to try to apply them to a specific challenge or problem. […] Based on our reading, however, a grand edifice may never be erected along the lines of, for example, neoclassical economics. If this is the case, it may be that we need to become better accustomed to a network-oriented model of how knowledge and ideas relate to each other.

For me, it is intriguing how the science of complexity not only defies scientific practices by diverting from the pure deductive and inductive approaches and combining them but also evaded characterizations in ‘traditional’ scientific schemes such as the building mentioned above. This reminds me of the book ‘Complexity and Postmodernism’ by Paul Cilliers, which I started reading but I got stuck somewhere in the middle, overwhelmed by his theory and language. I hope that I will finish it some day and report on that here.

The authors also try to answer a number of questions around the topic of the application of complexity to development and what it means for example for international donors. A few quotes from the concluding remarks:

In our view, the value of complexity concepts are at a meta-level, in that they suggest new ways to think about problems and new questions that should be posed and answered, rather than specific concrete steps that should be taken as a result.

[…]

As well as use by implementing agencies, an understanding of complexity must also be built into the frameworks of the donors and others who hold the power to determine the shape of development interventions. This may be easier said than done – complexity requires a shift in attitudes that would not necessarily be welcome to many working in Northern agencies. For example, such a shift may require adjusting away from the ‘mechanistic’ approach to policy, or being prepared to admit that most organisations are learning about development interventions as they go along, or being transparent about the fact that taxpayers’ money may be spent on a project that does not guarantee results. It may mean having smaller, but better programmes.

[…]

At the start of our exploration, our view was simply that complexity would be a very interesting place to visit. At the end, we are of the opinion that many of us in the aid world live with complexity daily. There is a real need to start to recognise this explicitly, and try and understand and deal with this better. The science of complexity provides some valuable ideas. While it may be impossible to apply the complexity concepts comprehensively throughout the aid system, it is certainly possible and potentially very valuable to start to explore and apply them in relevant situations.

To do this, agencies first need to work to develop collective intellectual openness to ask a new, potentially valuable, but challenging set of questions of their mission and their work. Second, they

need to work to develop collective intellectual and methodological restraint to accept the limitations of a new and potentially valuable set of ideas, and not misuse or abuse them or let them become part of the ever-swinging pendulum of aid approaches. Third, they need to be humble and honest about the scope of what can be achieved through ‘outsider’ interventions, about the kinds of mistakes that are so often made, and about the reasons why such mistakes are repeated. Fourth, and perhaps most importantly, they need to develop the individual, institutional and political courage to face up to the implications.

I’d recommend anyone who works in international development and is interested in complexity to read this paper. It is a perfect entry point also for people with no background in complexity science.