Prompted by some work for a client I dived back into the literature on institutions this week. It was a fascinating journey and I have discovered some other the things I have known before and confirmed many of my suspicions with the project at hand. Indeed, the reading confirmed my view that most market systems development projects pay too little attention to the institutions in a country, given their massive importance in shaping economic development. There is too much focus on finding solutions to fixing problems in the short term.

What I found fascinating while reading is that the insights from the theories on institutions and on complex systems actually overlap really neatly, with maybe slightly different ways of approaching change but in a coherent and complementary way.

The New Institutional Economics perspective

Let’s start with the perspective of New Institutional Economics. According to that literature, humans have an inherent tendency to reduce uncertainty by structuring their environment. Uncertainty in human interactions is reduced by creating structures that allow people to expect a certain behaviour from others in a specific situation. For example, in a football match, one can expect the players to adhere to the formal and informal rules. The rules of the game constrain what behaviour the players are expected to adopt. They may not, for example, pick up the ball with their hands and run with it to the goal. In the social sciences, the structures that reduce uncertainties in human interactions are called institutions.

Through people’s efforts to reduce uncertainties, the institutional framework emerges from the interactions of people in a society over time. These interactions are shaped by the dominant beliefs in a society. Beliefs shape how people perceive reality and how they respond to it. Dominant beliefs are those held by people who have the power to shape policy in a society. According to North [1:2], belief systems provide “both a positive model of the way the system works and a normative model of how it should work”.

Institutions continuously evolve based on how actors who have influence over policy decisions make sense of their perceived reality, how they evaluate institutional performance and the subsequent intention of these actors to adapt the institutions to optimise economic outcomes. Institutional change occurs when people who are able to influence policy decisions perceive the current institutional framework as not performing effectively with regard to whatever measure of success they deem appropriate – generally in generating economic benefit for them and their social group. Significant change often happens when new actors are getting in a position of legitimacy, influence and power. Institutional change is far from quick and easy.

The Complex Systems perspective

Complex adaptive systems are networks of actors that continuously act, react and interact and dynamically shape their environment through this interaction. The behavior of individual actors is not predictable – one can only react to what is happening in the moment. Yet, when we look at our experiences in working in human systems, there is a clear sense that there are certain repeating and persistent patterns of behaviour that hardly change over time and, thus, can be used to anticipate how actors are likely to behave. One could say that these patterns are areas of stability that emerge out of continuous dynamic interaction. An example of such a stable pattern that I found in a market analysis I recently read is that farmers do not react changing demand but rather keep growing what they have always grown.

Over time, these stable patterns created by the dynamic interaction start to also shape this dynamic interaction because we start expecting people to behave in a certain way. The patterns create structures that compel or even require actors to behave in that particular way. To use the same example, if a farmer was to break out of the customary way of doing things he or she is most likely to get some social reaction to that – “this is the weird guy who always wants to be different.”

Some of these structures are further formalised over time and turn into organisations, regulations and legislation. Others remain tacit and informal, like customs and social norms. Complexity scientists call these structures attractors and boundaries. But in essence, they are what social scientists call institutions.

Why institutions are important

Both theories show how institutional constraints accumulate over time so an elaborate structure of informal and formal institutions emerges in each society. Institutions constitute ‘the rules of the game’ both on the level of personal interactions but also on the level of interactions among organisations, firms and government. Institutional structures determine how the competitive environment is shaped and, consequently, whether an economy is competitive. Institutions reduce transaction costs and create positive externalities, for example through the coordination of available knowledge in a society, which allows the specialisation of production. With that, institutions shape the incentive structure of companies, leading them for example to invest in innovation and development or rather hold back and try to protect their assets from being expropriated by government agencies.

Institutions are a necessary preconditions for markets to work effectively in the long run. Market exchanges are regulated and shaped by laws and regulations as well as local customs and norms. While many primitive forms of market can exist through personal transactions where trust is built by social relations only, many countries are held back by an inability to enable more sophisticated markets based on impersonal transactions. Impersonal transactions occur when people transact with those they do not know, do not necessarily relate to, or will never see face to face. Impersonal exchange depends on a range of institutions that protect the rights of suppliers and buyers.

What this means for economic development work

Institutions show a level of stability that can be used to determine a system’s disposition, i.e. it’s inherent qualities, and its propensity for change. In other words, understanding these system characteristics allows us to say in which way a system is more likely to change (or if it is likely to change at all). Over time, we can observe how this disposition changes. Institutional change is, however, strongly path dependent – the current institutional framework and its history define how institutions can change in the future.

There are slightly different takes on how to approach institutional change in complexity theory and in New Institutional Economics. Taking the two together is in my view very informative when looking at affecting institutional change.

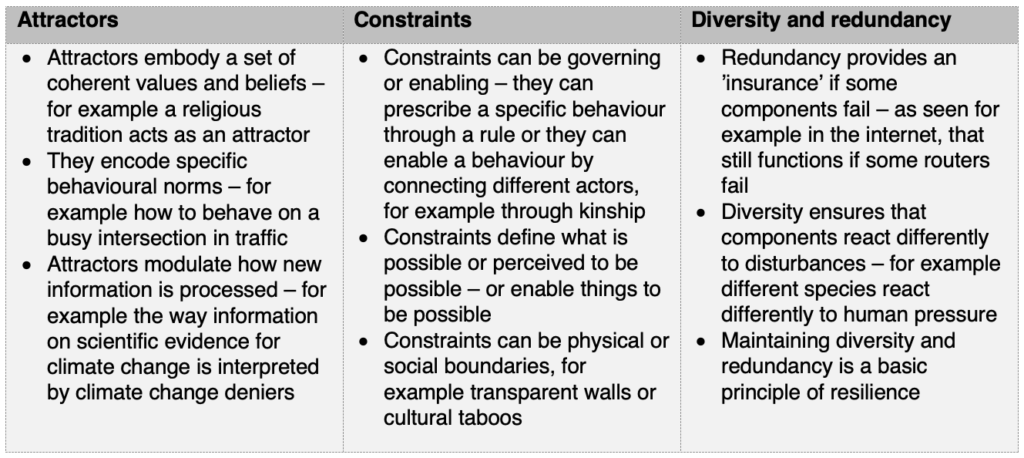

From a complexity perspective, two key concepts can be used to describe the structure of a complex system: attractors and constraints. A third important concept in complex systems is diversity. These concepts are described in the table below.

A change initiative can attempt to manage constraints, nudge existing or catalyse new attractors or manage diversity and redundancy within a system. A change initiative can achieve three things with that: move an attractor regime closer to a desired state (incremental), achieve a tipping point to a new attractor regime (catalytic), or manage diversity and redundancy to increase resilience.

From a New Institutional Economics perspective, institutional change is an intentional process shaped by actors who can achieve a certain amount of dominance through a combination of legitimacy, influence or power. As the beliefs of people or groups with power or influence have a dominant effect on the institutional landscape, development cannot be apolitical but needs to confront given power structures if it wants to achieve real change. So a political economy and power analysis is a central element to any economic change initiative.

Also due to path dependence of institutional change, institutional change needs to occur locally and the form of change cannot be imposed externally. The change that development agents deem necessary might not be possible given the history of how current institutions evolved. Path dependence makes institutional change generally an incremental rather than a radical process, so institutional change takes time.

Hence, change happens when the influential actors become aware of negative outcomes produced by the current institutional framework and act accordingly – or that other groups who have a more inclusive view on economic performance need to become more influential. Consequently, institutional change is best achieved when influential actors or networks of actors are made aware by development programmes of the institutional change process and their own role in it. These actors need to develop the capability to engage in, collectively discover and shape the evolutionary potential of the economy. This process is most effective when it is done in a transparent and participatory way; ideally all levels of society should have access to this process.

Changing institutions is not easy or quick and there is no simple recipe to do it. But a good place to start is to make the influential or potentially influential system actors more aware of the link between institutions, economic performance and inclusiveness. In Mesopartner, we often focus our work on the meso level (surprise!) and work with meso organisations to improve the way they assess the context and the way they provide services to their members and also how they interact with other organisations, including the government.

Two tools to map institutions

Here I would like to share two tools that I use in my work to help teams conceptualise and map the economies they work in, including the relevant institutions. I think it is important to have such a shared picture in a team to be able to discuss the situation with the same awareness and shared assumptions, being always mindful that the map is not the territory. These are not new tools and will have written about them before.

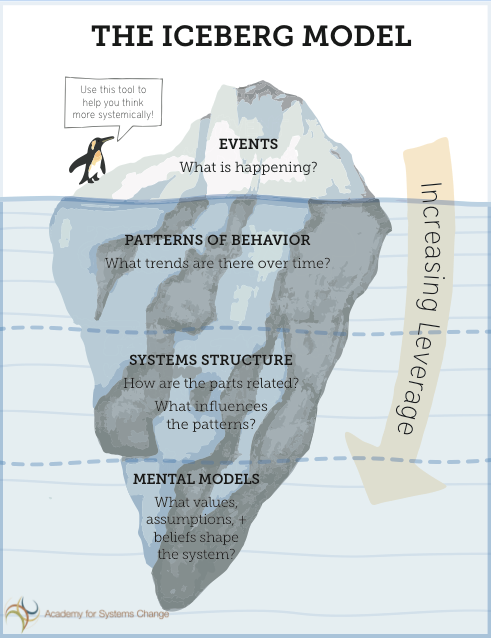

The first tool is the Systems Iceberg Model, which differentiates between what can be directly observed (the events and patterns that string these events together) and what shapes these patterns of events – the structures or institutions and their underlying mental models or paradigms. In New Institutional Economics, these mental models or paradigms are often called belief systems, as they represent the most fundamental beliefs in a society, such as for example the value of life or the role of humans in the world’s biosphere. Beliefs shape how people perceive reality and how they respond to it. This is reflected in the systems iceberg model shown below.

You can use the iceberg to map your system and will find that many institutions are mapped onto the systems structure level. This level can be further split up into physical infrastructure (terrain, roads, etc.), organisations (organisation as a form of doing things in a group itself being a form of institution), policies (laws, regulations, tax codex, etc.) and rituals (customs, norms, habits, etc.). The level of the mental models contains attitudes, beliefs, morals and values that underpin the structures.

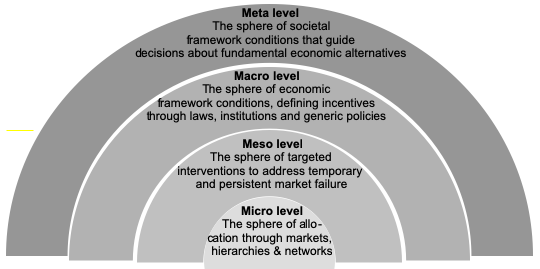

Another way to map institutions that is rooted in economic, social and political science theory is the Systemic Competitiveness Framework. It was developed in the German Development Institute (gdi) in the 1990s as a response to the Washington consensus. It is built on three important insights:

- Most successful countries were those that actively shaped locational and competitive advantages in a collaborative effort between the public and private sectors and the wider society

- These countries share an institutional structure that provides a specific business support environment in accordance with continuously emerging and changing requirements – not just broad brush macro-economic policies

- Economies in general are deeply embedded in the societies and prevailing culture in their respective locations

To reflect these insights and to understand the dynamics (or lack thereof) in economic change, two analytical layers were added in the framework to the macro and the micro levels of neo-classical economic orthodoxy:

- The meta level reflects that economies are deeply embedded in the societies in their respective locations and prevailing culture. The society needs to agree on the basic principles of orientation of economic development. The relevant actors (policymakers, businesses, civil society and also individuals) need to be able to organise and focus their strengths on the common goal of improving competitiveness as a means for economic development.

- The meso level is is conceptually positioned between the micro economy of interacting enterprises and the macro economic framework conditions. Policies and actors in the meso level shape the specific environment in which firms operate. The meso level is where both public and private actors at the national, regional and local level become involved in promoting business and where targeted policies, support initiatives and concrete projects are implemented jointly to promote locational advantages and increase relative competitiveness.

The main message of the framework is that purposeful economic development measures need to address each of the four levels. The meso level is especially important for strengthening the competitiveness of a territory and/or a specific sub-sector that has often been underestimated or ignored by economic development initiatives. In many developing economies, the meso level is very thin or even non-existent (read more about the framework and the importance in Mesopartner’s Annual Reflection 2017).

The Systemic Competitiveness framework can be used to break up the structural level of the iceberg and reveal the problematic patterns and the broader societal responses in a way that directly feeds into intervention options of economic development initiatives.

Title photo by Renate Vanaga on Unsplash

Another great blog Marcus. Thank you.

You run through existing literature seems to lean heavily on various forms of systems thinking. I got the impression when your spoke complexity you were talking about complex systems and probably complex adaptive systems.

What is your view on the arguments of Stacey & Mowles about why thinking of organisations as complex adaptive systems is problematic, which as I recall are essentially about boundaries and the role of autonomous individuals.

Hi John. I’m not too familiar with Stacey and Mowles’ work to be honest. I’m mainly drawing on what Dave Snowden calls the body of knowledge on anthro-complexity, which I think is slightly distinct from Stacey’s theory. In my view complexity principles apply to both organisations and whole societies, even though the dynamics are of course different as the number of people interacting are different. Dave recently wrote an interesting blog in which he mentions the number of people that can be part of an activity in obvious, complicated and complex situations (https://cognitive-edge.com/blog/mycorrhiza-abstraction-codification/).

I’m not familiar with anthro-complexity so should perhaps check it out. I have found it hard to find out what Snowdon’s actual theory is and perhaps would be able to find some answers to a nagging doubt that even the best theory provides and adequate theory about how organisations really function. Staceys Complex Responsive Processes seem to be much closer to my experience though.

It’s important, not just of theoretical interest, because our institutions that make up such large part of society are collapsing under the weight of their own administration.

I look forward to continuing to read you great blogs and learn from your experience.

Hi Marcus

Thanks for the comprehensive blog post. Like your previous articles I also thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

I am expecting to hear more on the institutional inertia to change stimulus from the complexity perspective. I have noticed this is the major problem hindering sustainable and systemic change proposed by market system development approach

A lot of institutional change is much beyond the time horizon of normal projects. It takes up to a generation to change some institutions. Our focus is really on improving the institutions of the meso space and the organisations that are expressing these institutions (e.g. education, R&D, skills development, technology transfer, etc.) and make them more responsive. But if the wider political environment is not conducive to that, this is very difficult.

Some times also donors make it difficult. We often see that meso organisations like chambers, business associations or regional development agencies are oriented towards the objectives of the donors rather than the needs of companies.