How does systems thinking and complexity theory help us in designing a global knowledge management facility?

A global knowledge management facility has the goal to manage knowledge within a specific community of practice in order to improve the application of that knowledge in general or of a specific approach in particular. From a traditional point of view, important activities of such a facility would be to collect and codify knowledge, analyze good practices and there might even be a wish for standardization of the application of this particular knowledge or approach. In this sense, the facility can be seen as a custodian of the ‘right’ knowledge and oversee and certify the quality of its application. It would guard the rigor or ‘pureness’ of application of the specific approach with a view to preserve or improve its effectiveness and efficiency.

With this picture in mind I read a chapter in a knowledge management book that describes implications of systems thinking and complexity theory on knowledge management from an organizational perspectives (Bodhanya 2008). I would like to apply the conclusions of the article to the design of such a global knowledge management facility.

In his article, Bodhanya describes differences in characterizing knowledge that stem from a number of debates within the scientific community revolving around the interplay between ontology and epistemology or, to put it in simpler terms, between perspectives of knowledge as a thing and knowledge as a dynamic process. According to Bodhanya, the current debates in knowledge management, however, reduce this pluralism of the discussion around knowledge because the dominant discourse is based on what he calls a cognitive-possession perspective. He terms this ‘first order knowledge management’.

First order knowledge management is built on the following assumptions (Bodhanya 2008:7):

- Knowledge is reified.

- Knowledge is useful when it is objective and certain.

- Distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge.

- Knowledge may be managed through knowledge management.

- Knowledge identification is a search process.

- Knowledge construction is a process of configuration.

- Knowledge management comprises knowledge processes such as identification, generation, codification, and transfer.

- Business strategy may be formulated and implemented. This is a fundamental assumption across all strategic choice approaches to strategy and, at a minimum, will include the design, planning, positioning, and cultural schools of strategy.

- Knowledge management strategy may be formulated and implemented.

- Knowledge management strategy must be aligned to the business strategy.

The concept of first order knowledge management seems in line with the goals and traditional activities of a global knowledge management facility as described above: “Ultimately, first order KM relies on knowledge processes such as knowledge identification, generation (or more accurately configuration), codification, capture, and transfer in order to develop human and social capital, as these are considered as important in facilitating productive activity” (Bodhanya 2008:8).

In his paper, Bodhanya argues against the view of knowledge as a thing and criticizes current knowledge management of gross oversimplifications by relying on a view on knowledge as something that can be possessed. He suggests that knowledge is a much more dynamic phenomenon and suggests instead to shift the focus from knowledge to the act of knowing itself. “Knowledge is only generated in the act of knowing; everything else is information. In other words there is the perpetual potentiality for knowledge generation, but this is only transformed into actuality when information comes into contact with the human intellect. This happens in the act of knowing in the instant when there is sensemaking and interpretation. (…) [H]uman actors are constantly engaged in thought, and hence are engaged in sensemaking and interpretation at every instant, so knowledge is being regenerated afresh at every instant. This phenomenon of constant thought and action means that there is perpetual regenerating of knowledge” (Bodhanya 2008:10). Based on these insights, Bodhanya constructs a ‘second order knowledge management’ that takes into consideration the dynamic interplay between knowledge and the knower. In second order knowledge management, he points out, more attention needs to be paid to the social interactions between actors.

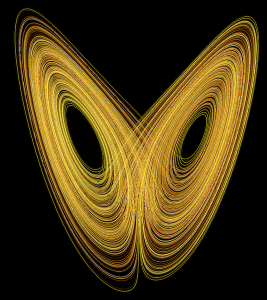

Bodhanya then details out how this view on knowledge and knowing is in line with systems thinking and complexity theory. An interesting debate he touches upon is the question who, from an organizational point of view, are the actors in a complex adaptive system of knowledge. The most obvious choice would be the individuals in an organization but another possibility is, for example, to see narrative themes as the actors. Bodhanya argues for a more nuanced view that includes the individuals as well as other forms of agents such as groups of individuals, departments, and human artifacts. He defines the systems of knowledge as ‘knowledge ecologies’: “A knowledge ecology is a dynamic system of heterogeneous agents that interact with each other according to their schemata. The schemata are inextricably linked to each agent’s propensity for interpretation and sensemaking on an on-going basis. Since interpretation and sensemaking are related to knowing in action, every act of interpretation and every act of sensemaking is in effect an actor creating knowledge. There are therefore multiple cognitive feedback loops being generated which in turn refresh the schemata according to which agents then act” (Bodhanya 2008:14). But he goes even further and looks for evolutionary tendencies in knowledge ecologies to an effect that knowledge structures become the primary agents that survive, vary, mutate, and are subject to retention and selection. There are, thus, various layers of interacting and interconnected complex adaptive systems with various types of actors at play, which makes the description – or prediction – of the system impossible.

Whereas first order knowledge management is based on a strategic choice view of business strategy, considerations of complexity and systems thinking show that the knowledge environment is far to complex for any one person to fully understand and, hence, to make strategic choices. This does not only change the view on knowledge management, but on business strategy itself; it shows the need for a more dynamic approach that is much more process oriented. “Alignment between business and knowledge management strategies may therefore not simply be designed and imposed, but may only be stimulated through managing organisational context and the interactions between actors within an outside the organisation. We may therefore also refer to business and knowledge management strategies as undergoing a process of co-evolution” (Bodhanya 2008:15).

What does this mean for knowledge management? First of all we have to realize that knowledge management does not have something to do with control over knowledge and its use. No single agent in a complex adaptive system can stand outside the system and direct it. “[M]anagerial orientations must shift from a preoccupation with the ordered, rational, analytical, and the fixed towards a tolerance of ambiguity, subjectivity, flux, and the transient nature of organisational life” (Bodhanya 2008:17). But this also means that there is no formula, recipe, or easy prescription on how to implement knowledge management. Rather, the conditions for the emergence of knowledge ecologies need to be developed. “The best that we can do is to facilitate rich interconnections between agents, increase agent diversity, and provide an enabling context for sensemaking and interpretation” (Bodhanya 2008:17). Bodhanya introduced an approach to second order knowledge management he calls strategic conversation, but he also points out that there is still a lot of research needed to fundamentally transform knowledge management into a systemic process co-evolving with other strategies within an organization.

One important piece of wisdom Bodhanya gives us for that journey: “As human actors and managers, we are in a sense deluded by the extent to which we think we are in control. It calls for increased humility on the part of all of us as human actors. In a systemic world, we control less than we think, because the effects of our actions are subject to many feedback loops and nonlinear responses that are outside our sphere of influence and control. (…) Our plans are merely artifacts, and to the extent that they contribute to co-evolution, they do have a valuable role. However, this may call into question our criteria for what the value of a plan is, and what constitutes a good or a bad plan” (Bodhanya 2008:19).

What does this all mean for a global knowledge management facility? Obviously, such a facility does not follow the same rules as an organization, which can be seen as complex adaptive system with a fairly obvious, if also penetrable, boundary. Knowledge sources are much more widespread and part of diverse organizations with their own agendas. One of the first insights, thus, must be that such a facility cannot exist on its own, observing, collecting knowledge, codifying it, and defining best practices, which it will then disseminate again into the system. Rather than a centralized secretarial-type entity, the facility should rather be a hub of a network of actors in the knowledge ecology with the aim to stimulate knowledge creation and exchange. As pointed out by Bodhanya, an essential step thereby is to “facilitate rich interconnections between agents, increase agent diversity, and provide an enabling context for sensemaking and interpretation” (Bodhanya 2008:17). So rather than to see the facility as a kind of library and custodian of the right kind of reified knowledge or the pure way of implementing an approach, it should much more be a place where discussions are stimulated and the knowledge is created while it is used. Thereby, diversity plays a big role. It is important to see that there is not one right way to implement an approach, but that knowledge is created from the diversity of its application.

This is just the beginning of a possible discussion and many things still need to be touched upon and many critical points in the assessment above need to be made visible and discussed. I hope, however, that this post provides some food for thought.

Reference: Shamim Bodhanya (2008): “Knowledge Management: From Management Fad to Systemic Change”. In: Abou-Zeid, El-Sayed: “Knowledge Management and Business Strategies: Theoretical Frameworks and Empirical Research.” Information Science Reference. Hershey, New York.